- FAQ

- An Introduction to Lime

- Introduction to Lime - Lime and its Production

Introduction to Lime - Lime and its Production

Tŷ-Mawr Posted this on 10 Jan 2023

|

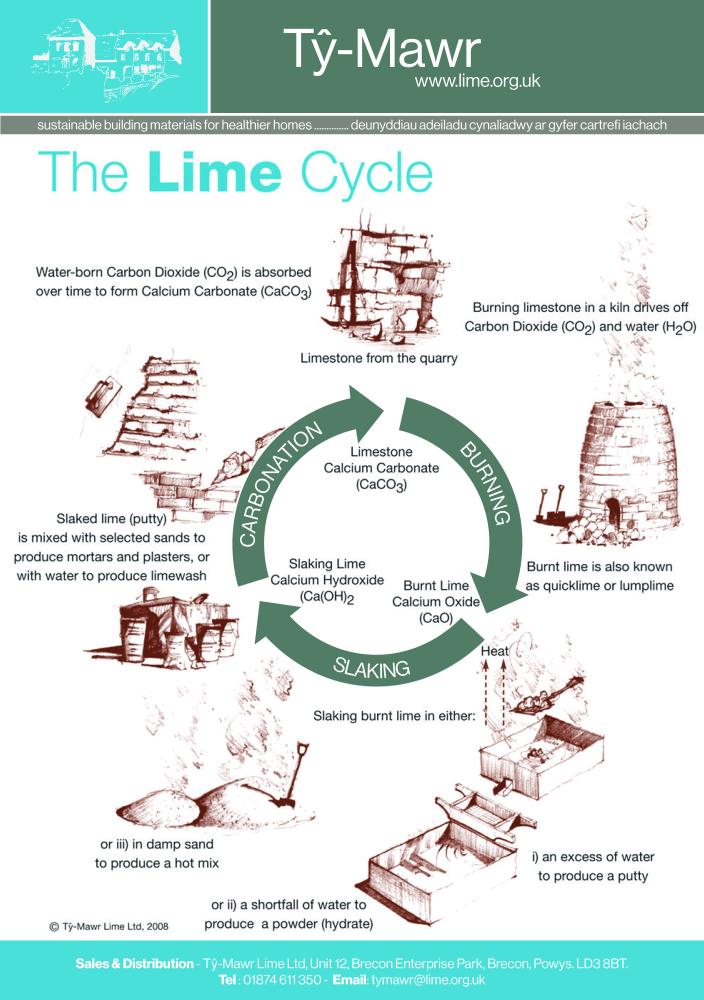

The Lime Cycle The lime cycle shows the stages from quarrying the limestone through to the production of mortars and plasters for our buildings and how it slowly, through the re-absorption of Carbon Dioxide, reverts to its original chemical form (Calcium Carbonate) in the wall. |

|

|

Lime Burning Limestone (Calcium Carbonate – CaCO3) is burnt in a kiln giving off Carbon Dioxide (CO2) gas and forming Calcium Oxide (CaO) which is commonly known as Quicklime or Lumplime. It needs to be burnt at 900°C to ensure a good material is produced. The temperature at which it is burnt will affect its reactivity in all other stages of the limecycle – slaking and carbonating. The resulting lime is at its most volatile and dangerous at this stage. |

|

|

Lime Slaking The Burnt Lime or Quicklime is then combined with water (slaked) as quickly as possible. From the moment it is burnt the material starts to degrade by ‘air-slaking’. Combining Quicklime (CaO) and water (H20) produces Calcium Hydroxide (Ca(OH)2 - slaked lime and heat. There are three main ways of slaking the Quicklime:

|

|

|

Lime Carbonation Lime sets by absorbing water soluble Carbon Dioxide from the air. This process is called carbonation. The ‘set’ or carbonation must occur slowly – the slower the set the better (it is not a case of just drying), therefore direct heaters or dehumidifiers do not help and may cause failures – it is therefore vitally important that the conditions are right to enable the water-borne Carbon Dioxide (CO2) to be absorbed. In our Lime Handbook, specific conditions are described to control the carbonation process. Failure to properly control carbonation will lead to problems and potentially failure on site. It is, therefore, an extremely important process to come to understand. |